During the school year, mental health sometimes gets put on the back burner as you add coursework, plan extracurricular activities, and live life in a way that is still somewhat new to you. According to the American Psychological Association, more than 60% of college students met the criteria for at least one mental health condition during the 2020-21 school year.

During college semesters, there are resources available on-campus and online – including Happier U, Journey to College’s initiative with the Missouri Department of Mental Health and Show Me Hop Crisis Counseling Program. Some of these resources may not be available when school is not in session. So what can you do to heal and help your mental health during the summer?

Summer is a perfect time for a break from school and have a much needed (and deserved!) mental health break. Take advantage of the warm days and sunshine to heal and help your mental health before fall, when everything picks back up again. A mental health break can be the best way for you to avoid burnout and re-energize yourself before it becomes time to take harder classes.

It is also a great time to refocus your mental health and figure out ways to incorporate good habits into your routine before the next semester rolls around. No matter how you choose to spend your summer, it is a good time to take a proactive approach to your mental well-being.

Here are some things that you can do during the summer to give yourself a mental health break and boost your mental well-being before the fall semester starts.

Celebrate Your Victories

It is easy to get caught up in the big victories of your college experience: getting scholarships, passing classes, and graduating. What about those small victories that add up throughout the semester? Did you give a really good presentation or successfully finish a large project? Did you manage to make it to every class during the semester, or even take a day off for your mental health?

It is easy to get caught up in the big victories of your college experience: getting scholarships, passing classes, and graduating. What about those small victories that add up throughout the semester? Did you give a really good presentation or successfully finish a large project? Did you manage to make it to every class during the semester, or even take a day off for your mental health?

Consider starting your summer with a celebration of all the tiny victories that helped you conquer the semester. Reflecting on your semester wins, no matter the size, is a great way to practice gratitude and celebrate a completed semester. If there is anything in particular that stands out from your successes, you can add them to your stockpile of tactics to get through a semester.

Try Various Relaxation Techniques

Relaxation techniques may seem daunting at first, but a little practice will improve your focus. Relaxation techniques include visualization, yoga, art therapy, journaling, breathing exercises, and so much more.

Relaxation techniques may seem daunting at first, but a little practice will improve your focus. Relaxation techniques include visualization, yoga, art therapy, journaling, breathing exercises, and so much more.

Without the stress of homework, late-night deadlines, and other college activities, summer is a perfect time to practice your relaxation techniques and incorporate them into your routine. As with any other skill, practice will improve these techniques and allow them to help you more. It also gives time for trial and error, as not every relaxation technique will work for everyone.

Do a Digital Detox

Even if you are doing a summer class or an internship, there is probably time during the summer to set down the devices and spend some time away from the screen. While this may seem like a suggestion to cut the cord completely for a while, you don’t have to go to extreme measures to take a mental health break during the summer.

Even if you are doing a summer class or an internship, there is probably time during the summer to set down the devices and spend some time away from the screen. While this may seem like a suggestion to cut the cord completely for a while, you don’t have to go to extreme measures to take a mental health break during the summer.

If you are taking summer classes, consider choosing a period of time each day or week to shut down the computer, put your phone on silent, and just step away for a bit. Want something a bit more drastic? Consider cutting out “modern technology”, however you define it, for 24 hours. This works really well if you find yourself without a schedule for a day or two and can carve out that time to drop any tech that has been in use for most of your life.

Seek Out Green (or Blue) Space!

W e all know that getting out into nature or green spaces helps, but did you know that Blue Spaces — places where you are near water — are also as beneficial to your mental health? It helps calm your internal state and can lead to fewer mental health issues in the long run.

e all know that getting out into nature or green spaces helps, but did you know that Blue Spaces — places where you are near water — are also as beneficial to your mental health? It helps calm your internal state and can lead to fewer mental health issues in the long run.

Summer is the best time of year for outdoor activities like swimming, hiking, soaking up some sun, and just being outside. It can also be a great time of year to explore Missouri State Parks and Conservation Areas. Just remember to use sun protection and hydrate when you are out and about this summer (especially if you are on any medicines for mental health). Even if you are not able to escape wherever you find yourself spending the summer, there is a chance that there is green or blue space near you!

Build your Coping Toolbox / Mental Health Toolkit

According to Mental Health America, a mental health toolkit, or as they call it, a coping toolbox is “a collection of skills, techniques, items, and other suggestions that you can turn to as soon as you start to feel anxious or distressed.” Without knowing it as a “coping toolbox,” you may already have some of these aspects at the ready for when things happen.

According to Mental Health America, a mental health toolkit, or as they call it, a coping toolbox is “a collection of skills, techniques, items, and other suggestions that you can turn to as soon as you start to feel anxious or distressed.” Without knowing it as a “coping toolbox,” you may already have some of these aspects at the ready for when things happen.

This toolkit may include breathing techniques, meditation strategies, comfort media, favorite stuffed animal, favorite foods, a blanket, affirmations (like the ones listed on the Happier U page), or a way to process your feelings (a journal, paper, chart).

The best thing about such a toolkit is that it doesn’t have to be all physical. Consider writing a list of resources and reminders in a notes app on your phone. You can also add online resources and phone numbers to contact when you need help.

In addition to the resources listed above, be sure to check out Happier U. There are resources located on that page for students to utilize, no matter the time of year, for mental health practices.

College-bound teens and young adults spend months preparing to go off to school. At this part of their journey, they are making decisions about meal plans and where to live, as well as class schedules and financial aid packages. These are not easy decisions. Even more difficult decisions and situations are to come once school starts. Although the focus is on the student during this time of major life change, it’s an important time for parents to take a step back and think: How can I be the best support system for my child during their college career, and foster a relationship built on trust? How can I help my child through a mental health crisis?

College-bound teens and young adults spend months preparing to go off to school. At this part of their journey, they are making decisions about meal plans and where to live, as well as class schedules and financial aid packages. These are not easy decisions. Even more difficult decisions and situations are to come once school starts. Although the focus is on the student during this time of major life change, it’s an important time for parents to take a step back and think: How can I be the best support system for my child during their college career, and foster a relationship built on trust? How can I help my child through a mental health crisis?

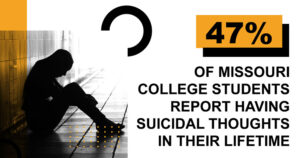

Here’s a daunting statistic about Missouri’s college students and mental health: one in four college students in the state have had suicidal thoughts in the past year. Upon hearing that, parents may turn a blind eye and say, “Yeah, but that’s not my kid.”

Here’s a daunting statistic about Missouri’s college students and mental health: one in four college students in the state have had suicidal thoughts in the past year. Upon hearing that, parents may turn a blind eye and say, “Yeah, but that’s not my kid.” For parents, it is so important to prioritize kids’ mental health just as you would physical health, and normalize seeking out help. Parents must look out for and care about all aspects of their child’s mental health in order to properly address suicide prevention. This includes whether or not their child is interacting with substances, if they are caring for their bodies, and if they know how to access and ask for services before they get to college. Joan encourages parents to equip their child with tools such as the ability to recognize if something is physically or mentally not right with their body, when to reach out and get help, how to resist self-medicating, and how to advocate for themselves.

For parents, it is so important to prioritize kids’ mental health just as you would physical health, and normalize seeking out help. Parents must look out for and care about all aspects of their child’s mental health in order to properly address suicide prevention. This includes whether or not their child is interacting with substances, if they are caring for their bodies, and if they know how to access and ask for services before they get to college. Joan encourages parents to equip their child with tools such as the ability to recognize if something is physically or mentally not right with their body, when to reach out and get help, how to resist self-medicating, and how to advocate for themselves. “Normalize mental health services and talk to your kids about what they are feeling and what they are thinking about, and ask if they need assistance with mental health care,” Joan says. “Create an ‘In this house, we seek therapy’ environment to take down the stigmas.”

“Normalize mental health services and talk to your kids about what they are feeling and what they are thinking about, and ask if they need assistance with mental health care,” Joan says. “Create an ‘In this house, we seek therapy’ environment to take down the stigmas.”